Where I work, we use D2L Brightspace as our LMS. We also used to use Insights, their data dashboard product, but we didn’t find value in it and turned it off in 2016 or so (just as they were revamping the product, which I think has gone through a couple of iterations since the last time I looked at it). The product in 2016 was not great, and while there was the kernel of something good, it just wasn’t where it needed to be for us to make use of it at the price point where we as an institution would see value. I will note, that we also weren’t in a place where as an institution we saw a lot of value in institutional data (which has changed in the last few years).

Regardless, as a non-Performance+ user, we do have access to D2L’s Data Hub, which has somewhat replaced the ancient Reporting tool (that thing I was using circa 2013) and some of the internal data tools. The Data Hub is great, because it allows you access to as much data as you can handle. Of course, for most of us that’s too much.

Thankfully, we’re a Microsoft institution, so I have access to PowerBI, which is a “business intelligence tool” but for the sort of stuff that I’m looking for, it’s a pretty good start. We started down this road to understand LMS usage better – so the kind of things that LMS administrators would benefit from knowing: daily login numbers, aggregate information about courses (course activation status per semester), average logins per day per person and historical trending information.

The idea is that building this proof-of-concept for administrators, we can then build something similar for instructors to give them course activity at a glance, but distinct from the LMS. Why not just license Performance+ and manage it through Insights report builder? Well, fiscally, that’s more expensive than the PowerBI Pro licensing – which is the only additional cost in this scenario. Also Insights report builder is in Domo, and there’s frankly less experts in Domo than PowerBI. Actually, the Insights tool is being revamped again… so there’s another reason to wait on that potential way forward. Maybe if the needs change, we can argue for Performance+, but at this time, it’s not in the cards, as we’d need to retrain ourselves, on top of migrating existing workflows, and managing different licenses. It would probably reveal an efficiency in that once built we don’t have to manually update, and it’s managed inside the LMS so it’s got that extra layer of security.

Where I’m at currently is that I’ve built a couple reports, put that on a PowerBI dashboard. Really, relatively simple stuff. Nothing automated. Those PowerBI reports are built on downloading the raw data in CSV format from Brightspace’s Data Hub, once a week, extracting those CSVs from the Zip format (thankfullly Excel no longer strips leading zeros automatically, so you could migrate/examine the data in Excel as a middle step), placing them in a folder, starting up PowerBI then updating the data.

The one report that I will share specifics about is just counting the number of enrollments and withdrawls each day, but every report we use follows the same process – download the appropriate data set, extract from Zip, place it in the correct folder within the PowerBI file structure on a local computer. PowerBI then can publish the dataset to a shared Microsoft Teams so that only the appropriate people can see it (you can also manage that in PowerBI for an extra layer of security).

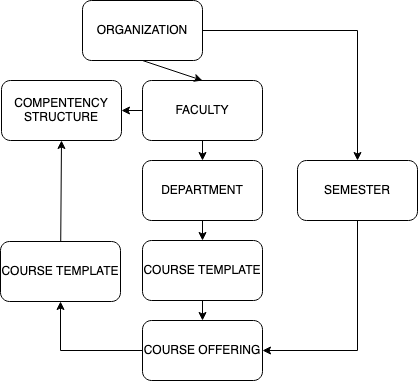

I obviously won’t share all the work we’ve done in PowerBI as well, some of the data is privileged, and should be for LMS admins only. However, I can share the specifics of the enrollments and withdrawals counts report because the datasets we need for enrollments and withdrawals is, not shockingly, “Enrollments and Withdrawals” (not the Advanced Data Set). We also need “Role Details”, to allow filtering based on roles. So you want to know how many people are using a specific role in a time period? You can do it. We also need “Organizational Units” because for us, that’s where the code is which contains the semester information for us and if we ever need to see a display of what’s happening in a particular course, you could. Your organization may vary. If you don’t have that information there, you’ll need to pull some additional information, likely in Organizational Units and Organizational Parents.

In PowerBI you can use the COUNTA function (which is similar to COUNTIF in Excel) and create a “measure” for the count of enroll and a separate one for the unenroll. That can be plotted (a good choice is a line chart – with two y-axis lines). Setup Filters to filter by role (translating them through a link between enrollments and withdrawals and role details).

I will note here, drop every last piece of unused data. Not only is it good data security practice, but PowerBI Pro has a 1 gig limit on it’s reporting size, which is a major limitation on some of the data work we’re doing. That’s where we start to actually get into issues, in that not much can be done to avoid it when you’re talking about big data (and the argument for just licensing Performance+ starts to come into play). While I’m a big fan of distributing services and having a diverse ecosystem (with expertise being able to be drawn from multiple sources), I can totally see the appeal of an integrated data experience.

Going forward, you can automate the Zip downloads through Brightspace’s API, which could automate the tedious process of updating once a week (or once a day if you have Performance+ and get the upgraded dataset creation that’s part of that package). Also, doing anything that you want to share currently requires a PRO license for PowerBI, which is a small yearly cost, but there’s some risk as Microsoft changes bundles, pricing and that may be entirely out of your control (like it is where I work – licensing is handled centrally, by our IT department – and cost recovery is a tangled web to navigate). Pro licenses have data limits, but I’m sure the Enrollments data is sitting at 2GB, and growing. So you may hit some data caps (or in my experience, it just won’t work) if you have a large usage. That’s a huge drawback as most of the data in large institutions will surpass the 1GB limit. For one page of visualizations, PowerBI does a good job of remembering your data sanitization process, so as long as the dataset itself doesn’t change, you are good.

Now, if you’re looking to do some work with learning analytics, and generate the same sort of reports – Microsoft may not be the right ecosystem for you as there’s not many (if any) learning analytics systems using Microsoft and their Azure Event Hubs (which is the rough equivalent of the AWS Firehose – both of which are ingestion mechanisms to get data into the cloud). That lack of community will make it ten times harder to get any sort of support and Microsoft themselves aren’t particularly helpful. In just looking at the documentation, AWS is much more readable, and understandable, without having a deep knowledge of all the related technologies.